Once you have consulted with your client and he has given you all the details of his invention it is advisable that you start with the drafting of the claims. To draft the claims you must establish what the invention is. In general, people think of an invention as something tangible. However, inventions are concepts.

IPWorkspace

Friday, 30 June 2023

Determining the Invention

Tuesday, 4 April 2023

Fair Use in Copyright

Section 107 of the Copyright Act

Wednesday, 1 February 2023

Plascon-Evans Paints Limited v Van Riebeeck Paints (Proprietary) Limited

(Appellate Division)

Coram: Corbett, Miller et Nicholas, JJA, Galgut et Howard, AJJA.

Date of hearing: 27 February 1984.

Date of judgment: 21 May 1984.

Judgment

Corbett JA:

1.

Appellant With Trade Mark Micatex

Appellant, a company dealing in paints and allied products, is the proprietor of a trade mark registered in terms of the Trade Marks Act 62 of 1963 ("the Act"). The trade mark in question consists of the word "Micatex". It was registered on 13 September 1971 in respect of the following goods falling within class 2 of the fourth schedule of the Trade Marks Regulations, 1963 (the regulations current at the time of registration):

"Paints, varnishes (other than insulating varnish), enamels (in the nature of paint), distempers, lacquers, preservatives against rust and against deterioration of wood and anti-corrosives, all containing mica".

Wednesday, 9 November 2022

Filing a Patent Application Online in the US

You must have your specification and drawing files prior to filing ready for uploading in pdf form.

You must also first download and fill in the files you want to submit and upload as part of the filing process using the electronic filing system. The files can be downloaded from https://www.uspto.gov/patents/apply/forms

Right-click on the link to the form and select “Save link as” or equivalent.

The forms that are going to be uploaded together with the specification and drawings of the patent in this example are:

1. Application Data Sheet or aia0014.

2. Oath or Declaration filed or aia0001.

3. Certification of Micro Entity (Gross Income Basis) or aia0015a.

https://www.uspto.gov/patents/apply

The file online links can be seen in figure 1:

Fig. 1: The File Online Links of the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO).

Click on EFS-Web for Unregistered eFilers.

A first new window for unregistered efilers opens as shown below in figure 2:

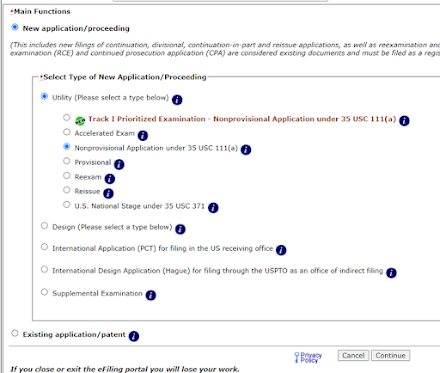

Complete last, first name, and e-mail address. Under Main Functions select New application/processing. Figure expands as shown in figure 3 below:

Click Upload & Validate.

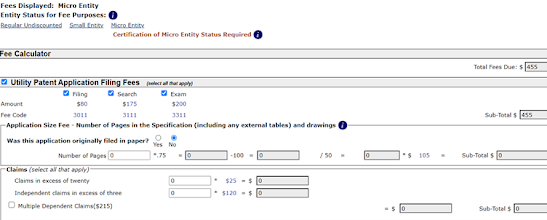

The upper or top part of the 4th new window is shown below in figure 8.

Sunday, 16 October 2022

Patent Application Preparation

Firstly, one may ask what are inventions? People, generally think of inventions as tangible things that can be seen. They see the invention as the new more fuel-efficient internal combustion engine, the newly manufactured substance such as a more cost-effective cleaning agent or the battery having a higher energy density and storage capacity. These, however, are mere embodiments of the invention. The invention is not something physical, but a concept. The invention is not something tangible but an abstraction. To protect an invention has to be defined. Definitions are always abstractions. The abstraction is referred to the inventive concept. It is the patent drafter’s task the define the inventive concept present in the embodiment of the inventor. The inventive concept should then be set out in the patent claims. (Slusky, 2012 (2nd ed.)) on page 3.

|

| FIG. 1: More Fuel-Efficient Internal Combustion Engine |

| FIG. 2: Patent to be Drafted Soon as Possible. |

.jpg) |

| FIG. 3: Invention Contained in Technical Drawings. |

| FIG. 4: The inventor is the Person Who Conceived the Invention. |

Saturday, 17 September 2022

Utility In Patent Law

Title 35 of United States Code section 101 (35 U.S.C. 101) states: “Whoever invents or discovers any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, ….”

Thus, 35 U.S.C. 101 serves to ensure that patents are granted on only those inventions that are "useful." Further, Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution authorizes Congress to provide exclusive rights to inventors to promote the "useful arts."

Figure

2: No Assertion of Specific and Substantial

Utility Claims to be Rejected.

Specific Utility

Wednesday, 7 September 2022

Inventive Step or Nonobviousness

Another requirement for patentability is that the invention must have an “inventive step” or is “nonobvious.”

An inventive step or nonobviousness means

that an invention must not have been obvious to a “person skilled in the art”

or one “of ordinary skill in the art.” It can be said obviousness means that if

any person of average skill in the scientific or technical field of the

invention could have put together different pieces of known information and

arrive at the claimed invention, then that invention is not patentable.

Objective evidence relevant to the issue of obviousness must be evaluated.

Such evidence, is sometimes referred to as "secondary considerations."

Secondary considerations may include evidence of commercial success, long-felt

but unsolved needs, failure of others, and unexpected results. The evidence

relevant to nonobviousness may be included in the specification as filed,

accompanying the application on filing. The evidence may also be provided in a timely

manner at some other point during the prosecution.

A Person Skilled in the Art

Sometimes, this hypothetical “person” should be presumed to be a

group of persons or a team of specialists, each of whom has a particular skill. The level of skill and knowledge of a person skilled in the art may

vary depending on the particular technical field involved. In general, the

level of knowledge and skill of the person skilled in the art is not the average of a layperson (i.e., the

minimum knowledge and skill) or a leading specialist’s skill (i.e., the maximum

knowledge and skill). The person skilled in the art is rather the skill

expected of an ordinary, duly qualified practitioner in the relevant field.

Reasoning That May Support a Conclusion of Obviousness

The following may conclude that the purported invention is obvious:

(A) Combining prior art elements according to known methods to yield

predictable results;

(B) Simple substitution of one known element for another to obtain

predictable results;

(C) Use of a known technique to improve similar devices (methods, or

products) in the same way;

(D) Applying a known technique to a known device (method, or

product) ready for improvement to yield predictable results;

(E) "Obvious to try" – choosing from a finite number of identified,

predictable solutions, with a reasonable expectation of success;

(F) Known work in one field of endeavor may prompt variations of it

for use in either the same field or a different one based on design incentives

or other market forces if the variations are predictable to one of ordinary

skill in the art;

(G) Some teaching, suggestion, or motivation in the prior art that

would have led one of ordinary skill to modify the prior art reference or to

combine prior art reference teachings to arrive at the claimed invention.

MPEP. (2020, 06 25). 2141 Examination Guidelines for Determining Obviousness Under 35 U.S.C. 103 [R-10.2019]. Retrieved 08 24, 2022, from Manual for Patent Examining Procedure: https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s2141.html

WIPO. (2022). WIPO Patent Drafting

Manual (Second ed.). Geneva, chemin des Colombettes, Switzerland: World

Intellectual Property Organization. doi:10.34667/tind.44657

Determining the Invention

Once you have consulted with your client and he has given you all the details of his invention it is advisable that you start with the draf...

-

1. The Alice Corp Patents The Alice Corporation is the owner of several patents that disclose schemes to manage certain forms of financial ...

-

(Appellate Division) Coram: Corbett, Miller et Nicholas, JJA, Galgut et Howard, AJJA. Date of hearing: 27 February 1984. Date of judgment: ...

-

Section 107 of the Copyright Act FIG. 1: Section 107 of the Copyright Act Defines Fair Use The United States Code, Title 17 contains the co...